Bit of a gap since my last blog, no real reason other than a break for summer holidays and then simply getting out of the habit/routine.

Life in Pop’s wood has taken a very definite turn towards autumn with a litter of leaves now covering a lot of the ground. The hornbeams are first out of the traps in the spring and are usually the first to lose their leaves in the autumn. Unlike the oak or beech that keep some of their withered leaves on throughout the winter; the hornbeams drop everything and stand bare against the sky from now onwards.

Lots of fungal growth some of which is quite exotic and others that are amazingly prolific. One such fungus that I had noticed back in September is apparently very common amongst fallen trees particularly oak. So no surprise that the fallen turkey oak is a great space for them to proliferate.

These are called Black Bulgar or Batchelor’s Buttons, this fungus grows in groups on fallen timber. It has black flat-topped discs with brownish tightly rolled over edges when young, and gradually opens up to become more cup-shaped up to 1½” across. It feels rubbery but watch out as the black spores that are produced on the upper surfaces come off and blacken your fingers.

The more exotic is shown below:

I have no idea what this is called but it looks wonderful.

These last few weeks I have been concentrating on chopping the large sections of oak into stackable firewood that can be left to dry out (season) over the winter and then be sold next autumn. In commercial terms I guess that I have contrived to do just about everything that adds cost to the final product. But am a bit wiser for next time, immediate thoughts :

- Cut the large sections of the trunk and branches into the final length right at the point tackling the fallen tree. Lengths of say between 10″ and 12″ make them suitable for domestic use. The temptation was to try and process the main trunk quickly by chainsawing large sections (hoops) off at a time but this had led to the need for secondary cutting which I am now having to complete.

- Process the wood as promptly as possible so that the finished firewood has time to dry out during the summer. Clearly the more surface area that is exposed to the sun and air the better and the quicker the moisture levels will drop to say below 20%.

- Ideally the wood would be stacked immediately adjacent to the point at which it is to be loaded for transport to market. This is a choice as to whether to make the wood very accessible for yourself (and anyone else who fancies lifting it onto a truck) and creating the need to double handle the logs. I have opted for security and have stacked the wood away from the entrance to the wood and will simply have to move it again nearer the time for sale

In order to prevent the wood piles becoming soaked very time it rains or snows I have made some crude canopies from polythene sheeting (packaging from a mattress) and the hazel poles harvested from my hazel coppice trial last year. This should hold off most of the weather and allow the wood to season over the winter.

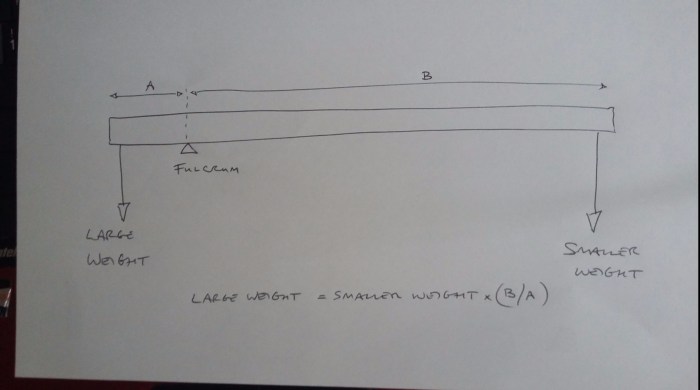

Hopefully next spring I will have assembled the solar log drying kiln on site and will be able to accelerate some of this process. More next time.